Truth--or Consequences?

I have a problem. I would like to have my cake, and eat it, too. To put the problem more formally, I would like to maintain

- that truth matters (I abhor epistemological and moral relativism[1])

- that Torah (as I understand it) teaches truth in some non-trivial fashion and that traditionally observant Judaism[2] is the only form of Judaism that has a chance of long-term survival

I also want to maintain

- that other forms of Judaism (and forms of traditionally observant Judaism that often annoy me deeply) are Jewishly genuine and must be treated with respect (and not just “tolerated”).

Can I indeed have the first two of these, and also the third? On the face of it, it would seem that I want to eat my cake, save it, and not even gain weight in the process. Medieval philosophers, Maimonides prominent among them, were convinced that truth is one, objective, unchanging, and accessible. In such a world, error is unforgivable and those with whom one disagrees are at best weak-minded and at worst evil—thus the wars of religion. In our postmodern world, epistemological (and moral) pluralism is often seen as a positive value. On the one hand, this undercuts actual warring over ideas; on the other hand, it makes serious conversation impossible: We are all talking past each other and about different things.

Is there no way out of this impasse? In the past, I have argued that what is needed is a form of epistemological modesty: affirming the truth of one's positions, while admitting that one might be wrong (but not actually thinking so).[3] In the present essay, I want to expand on this idea. This is not simply tolerance: I am not interested in tolerating other views, but in respecting them. Nor is this pluralism: I do not want to say that all views are equally true (which basically means that they are all equally false).

Several years ago I read a book by Jonathan Haidt (The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion), which resonated with me deeply. Haidt shows that our deepest convictions are rarely (if ever) the result of rational argument. Rationality, he maintains, is primarily used to justify our antecedently held positions, positions that are the result of many factors, rational argument often the least of them. Haidt helped me to understand why it is that people whom I respect (and often love) hold views that to me are clearly and evidently wrong. In their eyes, my views are equally wrong (about which, "of course," they are wrong).

The upshot that I took away from the book (which may or not have been Haidt's intention—please do not blame him for what I write here) is that we are not likely to convince people with whom we disagree over political or religious issues to give up their views, admit the falsity of those views (which Maimonides says will happen to the Gentiles in the messianic era), and accept the truth of ours. That is truly a messianic desire. Rather, realistically, we should look for common values and areas where we can work together, while agreeing to disagree about many important issues. Despite Haidt, I am an epistemological messianist (i.e., a Maimonidean messianist)—I believe that eventually reason will win; I just do not see it happening anytime soon. In the meantime, if we really want Jews and Judaism to survive, we have to get along. Getting along does not mean agreeing; I have no doubt but that my take on Judaism is correct, but I also realize that I might be wrong. In the meantime, we have lots to do.

Let me be clear: I am convinced and believe that much of what is called Jewish Orthodoxy today (in its manifold varieties) is closer to the Judaism of the last two millennia than other "denominations" and is of them all the most likely to survive into the future. This conviction and belief is constantly strengthened by the ways in which Conservative and Reform Judaism are becoming ever less traditional. But, I am aware enough of Jewish history to know that I might be wrong: It is only in retrospect that we now know that Pharisaic Judaism was destined to be the future of Judaism, not the Sadducees, not the Essenes, not the Zealots, and certainly not the Nazarenes. As Yogi Berra famously said, "It is tough to make predictions, especially about the future."

I want to add a few more words about what I learned from Haidt. I am basically a liberal on most issues. This is clearly a matter of upbringing (in the Orthodox Jewish home in which I was raised, there were things Jews never did: violate Shabbat, eat treyf, cross picket lines, and never, never vote Republican). It is also a matter of personality: I am pretty much a live and let live kind of fellow. It turns out, when I look back on it, that my liberal orientation was clearly established long before I knew of the tensions between liberty (a virtue often prized by conservatives) and equality (a virtue often prized by liberals), between freedom and organization. Even now, when all too many self-declared liberals ("progressives" in today's PC-talk) hate Israel (and by extension hate me), I cannot be comfortable in the conservative camp. Jonathan Haidt helped me to understand that conservatives cannot help themselves (any more than we liberals can help ourselves). That being the case, what point can there be in arguing over these issues?

Now it is obviously the case that people do change their minds. Many are familiar with Irving Kristol's gibe that neo-conservatives are liberals "mugged by reality." But how often does this actually occur? There are a tiny number of cases of quasi-"religious" conversion, as it were, and a somewhat greater number of cases of people dragged, kicking and screaming as it were, from one position to another. But this is usually a very long process, and how often does it really happen? In my experience, only rarely.[4]

Similarly, it seems to me that different takes on Judaism on the part of different sorts of Jews are not arguments over facts or their interpretation. When each group insists that only it knows the truth, that only it truly represents the message of Sinai, constructive conversation becomes impossible. We should learn to disagree, but join hands when we can—there are certainly enough challenges facing the Jewish people to give each and every one of us plenty to do together.

To my mind, there is nothing new about this; it is the way Judaism has always worked. Had Descartes been Jewish, he would have said, "We argue, therefore we are." As I will try to illustrate, I mean something more than a trite reference to the culture of talmudic mahloket, something more than trotting out "these and these are the words of the living God"—I mean something deeper.

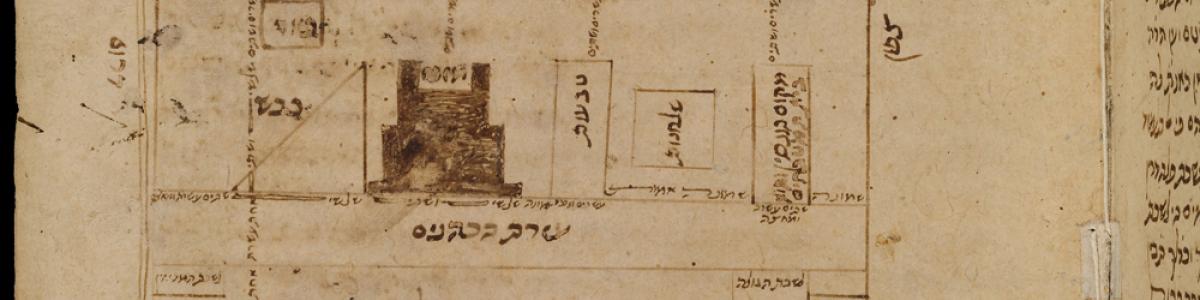

I am writing these words during the summer months, which means that we are reading Sefer Bemidbar (the Book of Numbers) in the synagogue. Recently, I came across Rashi on Numbers 8:4. The Torah there says, According to the pattern that the Lord had shown Moses, so was the lampstand [menorah] made. On this passage Rashi writes: "God showed Moses with His finger [how the menorah was to be made], as Moses had difficulty [visualizing it]." Did Rashi really believe that God has fingers? We will never know. What is clear, however, is that Rashi was not troubled by the fact that his readers might easily understand him to think that God has corporeal form. He simply seemed to have no problem with the issue. Thus, in two other places in Sefer Shemot (the Book of Exodus, 7:5 and 14:31) Rashi tells us that references to God's hand are to yad mamash, "a hand actually." In these cases, he may not have meant to be taken literally, but, again, he certainly had no qualms about that possibility. Indeed, I will show below that there is good reason to believe that Rashi might well have thought that God actually had hands and fingers.[5] But first, let us see what Maimonides says about this matter.

In "Laws Concerning Repentance," III.6, Maimonides writes that "The following have no portion in the world to come, but are cut off and perish, and for their great wickedness and sinfulness are condemned forever and ever." In paragraph 7, he specifies one of the groups of people here mentioned:

Five classes are termed sectarians [minim]: he who says that there is no God and that the world has no ruler; he who says that there is a ruling power but that it is vested in two or more persons; he who says that there is one Ruler, but that He has a body and has form; he who denies that He alone is the First Cause and Rock of the universe; likewise he who renders worship to anyone beside Him, to serve as a mediator between the human being and the Lord of the universe. Whoever belongs to any of these five classes is termed a sectarian.[6]

On this text, Maimonides' acerbic critic, R. Abraham ben David (Rabad), writes:

Why has he called such a person [he who says that there is one Ruler, but that He has a body and has form] a sectarian? There are many people greater than, and superior to him, who adhere to such a belief on the basis of what they have seen in verses of Scripture, and even more in the words of the aggadot, which corrupt right opinion about religious matters.[7]

I do not believe that Rabad was affirming the corporeality of God (after all, those who do believe in divine corporeality are misled by Torah verses and aggadot that “corrupt right opinion about religious matters"); rather he was affirming that one is allowed to be mistaken about that issue. It would appear that Rashi might very well fall under the heading of people "greater than and superior" to Maimonides who got this matter wrong, or at the very least was unconcerned about possibly misleading others about the issue. But, according to Maimonides, if Rashi held that God has hands and fingers, then he is a min (sectarian) who has no share in the world to come![8] God's corporeality is an issue about which no one is permitted to remain mistaken, not even "children, women, stupid ones, and those of a defective natural disposition" (Guide I.35, p. 81).[9]

So, is Maimonides right? If so, is Rashi a heretic (at whom God is angry and whom God hates)?[10] If Rashi is not a heretic, does he have a share in the world to come, and is he arguing with Maimonides about this subject in heaven? If so, then was Maimonides, the greatest theologian whom Judaism has ever known, wrong about a core issue of Jewish belief?[11]

In a preface he kindly wrote for my book, Maimonides' Confrontation with Mysticism,[12] Moshe Idel pointed out that Maimonides and Judah Halevi, despite the many important differences between them as laid out in that book, could have prayed together in the same synagogue. Maimonides, I am sure, would be welcome in Rashi's shul, but I very much doubt that Rashi would have been made welcome in Rambam's synagogue.[13]

Let us use Rashi in Sefer Bemidbar for another example. In Numbers 12:1, Rashi seeks to explain aspects of Aaron and Miriam's criticism of their brother Moses. One of the objects of their criticism of their brother is that Moses had taken to wife "a Cushite woman." Rashi there indulges in unfortunate racism[14] and also explains part of the verse by reference to the evil eye, which he seems to take literally.[15]

I very much doubt whether Maimonides took the notion of evil eye in the literal way in which Rashi apparently presents it.[16] Be that as it may, I would be surprised if many readers of Conversations really believe in the power of the evil eye in the non-metaphorical way in which Rashi seems to take it. So, those of you readers of this article who do not believe in the evil eye: are you (and I) heretics (for denying something taught, with all apparent seriousness, in Talmud and Rashi), or are believers in the evil eye mistaken and perhaps simply superstitious? If the latter, what does that say about Rashi in your eyes, what does it say about your emunat hakhamim, about "da'as Torah"?[17]

Remaining with Sefer Bemidbar, I was struck by verse 14:42, where a group of Israelites sought to ascend to the Land (after the affair of the spies) without divine sanction. They were warned: Do not go up, lest you be routed by your enemies, for the Lord is not in your midst—and indeed they were routed by their enemies. It occurred to me that anti-Zionist Hareidim probably read that verse as a warning against Zionism. (Of course, thank God, it is our enemies, and not us, who are consistently routed, which undercuts any possible Hareidi reading of the verse—but, for them, as Herzl famously said, "If you will it, it is no dream.") Thanks to the successes of the State of Israel (and thanks to the Zionist taxes, which support so many Hareidim) the fundamental debate between Zionists and Hareidi non- and anti-Zionists is largely dormant today. But the debate is actually quite fundamental—one need not go as far as the Satmar Rebbe who blamed the Holocaust on the "sins" of Haskalah and Zionism to understand that in the eyes of Hareidim one who sees the State of Israel as having positive religious value (messianic or otherwise) is at the very least foolish and more likely sinful. If one also sees the State of Israel as the "first flowering of the messianic redemption," then, in Hareidi eyes, one violates the twelfth of Maimonides' Thirteen Principles of Faith, which adjures Jews to wait for the coming of the Messiah.

Continuing with my current reading, I recently came across a passage in Rav Kook's Orot[18] that really surprised me.[19] Rav Kook maintains that one who holds that all human beings are holy, that all are children of the Lord, that there is no difference between nation and nation, that there is no chosen and holy nation in the world, that all human beings are equally holy (the repetition is in the text), such a one is a follower of Korah and gives expression to the latest form of the sin of Cain. Rav Kook condemns this view in the strongest possible terms.

Okay, so I am an evil follower of Korah—but so is Maimonides.[20] One is tempted here to recall the late Yeshayahu Leibowitz's joking (?) claim that there are two inconsistent traditions in Judaism, one beginning with Moses, continuing through Isaiah, Rabbi Yishmael, Maimonides and on to Leibowitz himself, the second beginning with Korah, continuing through Ezra, Rabbi Akiva, Judah Halevi, the authors of the Zohar, Hassidut, and on to the two Rabbis Kook. But this is really no joking matter. As in the previous examples, we have here dramatically different views about core issues in Judaism, within what is ordinarily called Orthodoxy. These arguments are not about peripheral issues, nor can they be papered over. If truth is God's seal, and if we affirm "Moses is true, and his Torah is true,” we should not be able to look at such debates with equanimity, pretending that they are not important. But that is precisely what Jews have always done!

In making this claim, and in citing the examples above, I have, in effect, been following up the thrust of my book, Must a Jew Believe Anything?. In that book, I argued that historically Jews paid more attention to what people did than to what they thought, and that a focus on orthodoxy per se is a modern—and unfortunate—innovation.[21] If we insist on our version of Jewish truth alone, and reject competing views as illegitimate, then we must decide whom to admit to our Orthodox synagogues: Rashi or Maimonides, Rav Kook or Maimonides, those of us who accept superstitions or those of us who reject them, Zionists or non/anti Zionists. If we admit all of them (and give them aliyot!), how can we exclude the "Open Orthodox," Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, Reconformodox Jews? We simply cannot have it both ways.[22]

Of late, the issue has come to the fore dramatically. Rabbis, all of whom are ordinarily considered Orthodox, and who certainly look it, are more and more allowing themselves publicly to ask questions about the historicity of the biblical stories, about the nature of the Revelation at Sinai and about the morality of many biblical stories.[23] It is questions such as these that caused the late Louis Jacobs to be hounded out of English Orthodoxy.[24]

I foresee at least two immediate objections to my thesis in this essay. I will be "accused" of advocating orthopraxy, or social orthodoxy.[25] It will also be argued that however far apart Rashi and Rambam are theologically, for example, at least they both put on tefillin and kept kasher and that therefore their theological differences can be ignored, or at least minimized.

The first accusation is wrong: My argument here rests on the notion that emunah, faith, in Judaism is first and foremost a relationship with God, and not something defined by specific beliefs (Rambam, of course, to the contrary).[26] Biblical and talmudic Judaism were uninterested in theology per se, and also preferred practice for the wrong reason (she-lo lishmah), but only because it would lead to practice for the right reason (li-shmah) and this right reason certainly involved trust in God. Ruth said to Naomi: "Your people are my people"—but did not leave it at that; she immediately added: "Your God is my God." To all intents and purposes, Maimonides sought to change Judaism from a community, in effect a family, defined by shared history, shared hopes for the future, and a never clearly defined faith/trust in God, into a community of true believers. In other words, Maimonides reversed Ruth's statement and in so doing created Jewish orthodoxy. For the past 800 years this innovation has been both accepted and resisted. Accepted, at least pro forma, by all those Jews who think that Maimonides' Thirteen Principles define Judaism;[27] resisted, by all those Jews who refuse in practice to accept the consequences of this definition of Judaism, finding all sorts of excuses not to persecute (unto death) heretics.

The second objection involves a kind of self-contradiction, or circular reasoning. At bottom, it depends upon a notion of "orthodoxy" introduced into Judaism by Maimonides, but willfully ignores the issues which he himself thought most important. Of course, Rashi and Rambam would be made welcome in our synagogues (thank God for that!). But for Maimonides punctilious fulfillment of the mitzvoth does not make one Orthodox: only orthodoxy (=correct doctrines) makes one Orthodox.

Both objections to my argument here seek to have their cake, and eat it, too.

In conclusion: Can I hold on to traditional "Orthodoxy" (in terms of community and practice[28]) while refusing to reject non-Orthodox versions of Judaism out of hand? Sure, if I resist Maimonidean orthodoxy and return to the way in which Judaism was understood in Torah and Talmud.[29]

[1] As has been often noted, anyone who thinks that science is only a discourse is probably best off not flying on airplanes—successful air flight depends upon physics, not discourse. See further: Ophelia Benson and Jeremy Stangroom, Why Truth Matters (London: Continuum, 2006).

[2] I have no patience for the term “orthodoxy,” as anyone familiar with my book, Must a Jew Believe Anything?, 2nd edition (Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2006), will know.

[3] See: Jolene and Menachem Kellner, "Respectful Disagreement: A Response to Raphael Jospe," in Alon Goshen-Gottstein and Eugene Korn (eds.), Jewish Theology and World Religions (Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2012): 123–133.

[4] It happened to me after the intifada that began the year 2000. It took me a long time to realize that the Palestinian leadership was rejecting not the results of 1967, but the results of 1948, and that anti-Semitism is alive and well in circles with which I used to identify. For anyone who might be interested, see M. Kellner, "Daniel Boyarin and the Herd of Independent Minds," in Edward Alexander and Paul Bogdanor (eds.), The Jewish Divide Over Israel: Accusers and Defenders (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2006): 167–176.

[5] See the following two studies by Ephraim Kanarfogel, who basically agrees that the issue of divine corporeality was not a focus of medieval Ashkenzic thought: "Anthropomorphism and Rationalist Modes of Thought in Medieval Ashkenaz: The Case of R. Yosef Behor Shor," Jahrbuch Des Simon-Dubnow-Instituts = Simon Dubnow Institute Yearbook 8 (2009): 119–38 and "Varieties of Belief in Medieval Ashkenaz: The Case of Anthropomorphism," in Matt Goldish and Daniel Frank (eds.), Rabbinic Culture and Its Critics: Jewish Authority, Dissent, and Heresy in Medieval and Early Modern Times (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008), pp. 117–160. As Kanarfogel put it to me personally, the whole orientation and training of the Tosafists differed from that of philosophically trained Jews.

[6] I cite the translation of Moses Hyamson (New York: Feldheim, 1974), p. 84b.

[7] I cite the text as translated by Isadore Twersky, Rabad of Posquieres: A Twelfth-Century Talmudist (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1980), p. 282. A more moderate version of Rabad's gloss has been preserved. See my Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought: From Maimonides to Abravanel (Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1986), p. 89.

[8] It should be further remembered that for Maimonides to affirm God's corporeality is to deny God's unity, which is tantamount to denying the entire Torah (See Guide of the Perplexed III.29, p. 521; III.30, p. 523; and III.37, pp. 542 and 545 and, most especially, "Laws of Idolatry," II.4). Note further that in Guide, I.36 Maimonides teaches that affirming corporeality of God is worse than idolatry!

[9] Let it be noted that Maimonides, unlike almost all other medieval figures (Jewish, Christian, Muslim), held women to be fully human, fully created in the image of God. See Kellner, "Misogyny: Gersonides vs, Maimonides," in Kellner, Torah in the Observatory: Gersonides, Maimonides, Song of Songs (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2010), pp. 283-304. For whatever it might be worth, Maimonides' misogyny is halakhic, not philosophical.

[10] See the statement at the end of the 13 principles (Must a Jew Believe Anything?, pp. 173–174) and Guide I.36.

[11] For a convincing argument that Rashi may indeed have been a corporealist, see Natan Slifkin, "Was Rashi a Corporealist?"Hakirah 7 (2009): 81–105.

[12] Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2006

[13] This is actually unfair. There is much evidence that Maimonides suffered fools, if not gladly, at least patiently. See, for example, his account of his daily schedule in his famous letter to Samuel ibn Tibbon, translator of the Guide of the Perplexed into Hebrew, and, for another example, Paul Fenton, "A Meeting with Maimonides," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 45 (1982): 1–5. The letter to ibn Tibbon may be found in Leon D. Stitskin, Letters of Maimonides (New York: Yeshiva University Perss, 1977), pp. 130–136.

[14] A common trope in the Middle Ages. See Abraham Melamed, The Image of the Black in Jewish Culture: A History of the Other (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003).

[15] The Bar-Ilan Database cites a dozen places where Rashi uses the expression in his Bible commentaries. Given its widespread use in rabbinic texts (the Bar Ilan Database find the expression almost 150 times in rabbinic literature), there is no reason to think that Rashi did not take it literally.

[16] See Marc Shapiro, Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters (Scranton: University of Scranton Press, 2008), pp. 128–129 and 138. Shapiro, by the way, has a long discussion there of demons, about which the GR"A famously castigated Maimonides for rejecting what the GR"A thought of as an important talmudic belief. How many of readers of this essay believe in the actual existence of demons? Those of you who do not, are you still Orthodox?

[17] Further on Rashi and Rambam, see many of the articles in Ephraim Kanarfogel and Moshe Sokolow (eds.), Between Rashi and Maimonides: Themes in Medieval Jewish Thought, Literature, and Exegesis (New York: Yeshiva University Press, 2012).

[18] Jerusalem: Mossad Ha-Rav Kook, various printings.

[19] I was surprised because this passage seemed so inconsistent with other, more universalist, aspects of Rav Kook's thought. But perhaps I should not have been surprised. Rav Kook famously once wrote that the distinction between Jewish and Gentile souls is greater than the distinction between Gentile souls and animal souls (Orot, p. 156). Further on Rav Kook in this context, see the article by Hanan Balk (next note), pp. 7–8. For a recent, illuminating, study, see Yehudah Mirsky, Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).

[20] For one exemplary text, see "Laws of the Sabbatical Year and Jubilee," XIII.13. For support of this interpretation of Maimonides see my books: Maimonides on Judaism and the Jewish People (Albany: SUNY Press, 1991), Maimonides' Confrontation with Mysticism, and Gam Hem Keruyim Adam: Ha-Nokhri Be-Einei ha-Rambam (Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 2016). For (chilling) texts about the alleged ontological superiority of Jews over Gentiles, see: Hanan Balk, "The Soul of a Jew and the Soul of a Non-Jew: An Inconvenient Truth and the Search for an Alternative," Hakirah: The Flatbush Journal of Jewish Law and Thought 16 (2013): 47–76; Jerome Gellman, "Jewish Mysticism and Morality: Kabbalah and Its Ontological Dualities," Archiv fuer Religionsgeschichte 9 (2008): 23–35; and Elliot Wolfson, Venturing Beyond: Law and Morality in Kabbalistic Mysticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[21] For an influential sociological analysis of this innovation, see Jacob Katz, “Orthodoxy in Historical Perspective,” in P. Y. Medding (ed.), Studies in Contemporary Jewry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), vol. 2, pp. 3–17.

[22] One could add to this list the whole question of the legitimacy of Chabad. See David Berger, The Rebbe, the Messiah, and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference (London: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2001). I do not believe that there are many (if any) Orthodox rabbis who doubt the cogency of Berger's strictures of Chabad, but, at the same time, there appear to be none who follow him in accepting the consequences of their (apparent) acceptance of his critique. One could also argue—and indeed, I have argued, that the Judaisms of Maimonides and of Kabbalah are fundamentally irreconcilable. See my Confrontation (above, note 12).

[23] For an entry into this lively discussion, see

http://thetorah.com/torah-four-questions/. Two recent books by my friend Prof. Yehudah Gellman are exemplary of the new openness: God's Kindness Has Overwhelmed Us: A Contemporary Doctrine of the Jews as the Chosen People (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2013) and This Was from God: A Contemporary Theology of Torah and History (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2016). I await the third volume in this planned trilogy (about the morality of various biblical stories) with excitement. On this last issue see my "And Yet, the Texts Remain: The Problem of the Command to Destroy the Canaanites," in Katell Berthelot, Menachem Hirshman, and Josef David (eds.), The Gift of the Land and the Fate of the Canaanites in Jewish Thought (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014): 153–179.

[24] For Rabbi Jacobs' own take on the "affair," see:

http://www.masorti.org.uk/newsblog/newsblog/news-single/article/the-jacobs-affair.html#.WVpD7-lLeUk. A propos Louis Jacobs I am reminded of a statement attributed to the late Eliezer Berkovits: Why is it thought that one must accept a particular doctrine of torah min ha-shamayim (Torah from heaven) in order to have yir'at shamayim (awe of heaven)? This profound truth is relevant to the figures cited above in fn. 23.

[25] On the latter see Jay Lefkowitz, "The Rise of Social Orthodoxy: A Personal Account," Commentary Magazine, April 1, 2014 (https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/the-rise-of-social-orthodoxy-a-personal-account).

[26] This is the burden of my Must a Jew Believe Anything? as is the rest of this paragraph.

[27] Even if their only acquaintance with the principles is a Hebrew poem derived from the long Arabic text which Maimonides actually wrote). See Marc Shapiro, The Limits of Orthodox Theology: Maimonides' Thirteen Principles Reappraised (London: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004).

[28] Practice, of course, exists on a scale; unlike doctrine it does not admit of black/white, true/false, in/out, faithful/heretic. There is a near-infinite number of gradations of halakhic observance, and no one, not even Moses, gets it perfect (on which, see, for example, Rashi on Nu. 31:21).

[29] Several kind friends argued with me over various aspects of this essay. My thanks to Hanan Balk, Jolene S. Kellner, Tyra Lieberman, Avrom Montag, Zephaniah Waks, and Alan Yuter.