This essay, by Rabbi Marc D. Angel, was originally published as the Introduction to the book he edited, “Exploring the Thought of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik,” published by Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, 1997, on behalf of the Rabbinical Council of America. This article appears in issue 12 of Conversations, the journal of the Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals.

The modern era in the Western world has witnessed numerous assaults on the patterns of traditional religious life. Science has changed the way people think; technology has changed the way they live. Autonomous, human-centered theology has come to replace heteronomous, God-centered theology. Rationalism and positivism have constricted metaphysics. Respect for authority and hierarchies has been replaced by an emphasis on individuality and egalitarianism. The challenges of modernity are symbolized by such names as Darwin, Schleiermacher, Freud, Einstein, Ayn Rand.

The modern era has also seen dramatic changes in the physical patterns of life: vast migrations from the farms to the cities; mass emigration (often as refugees) from one country or continent to another; shrinking family size; increased mobility; expansion of educational opportunities; phenomenal technological change.

Peter Berger has described modem individuals as suffering "spiritual homelessness." People have lost their sense of being part of a comprehensive, cohesive and understandable world.

For the Jewish people, the modern period has been particularly challenging. Jews were given the possibility of entering the mainstream of Western civilization. As the first winds of change swept into Jewish neighborhoods and ghettos, many Jews were enticed to leave traditional Jewish life behind. They hoped to gain acceptance into the general society by abandoning or modifying their religious beliefs and observances. Some went so far as to convert to other religions. The Haskalah--Jewish "enlightenment"--attracted numerous intellectuals who sought to modernize Jewish culture. The result was a secularization and objectification of Judaism.

The traditional religious framework was threatened by the Reform movement. Reform was an attempt of 19th century Western European Jews to "sanitize" Judaism by discarding Jewish laws and traditions. Reform wanted to make Judaism appear more "cultured" and socially respectable.

Whereas in previous eras, the masses of Jews accepted the authority of Torah and halakha, the modern period experienced a transition to the opposite situation--the masses of Western Jews no longer accepted the authority of Torah and halakha. In their desire to succeed in the modern world, many were ready to cast aside the claims of Jewish tradition. When large numbers of European Jews came to the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this phenomenon continued and expanded. A sizable majority of American Jews came to be affiliated with non-Orthodox movements or chose to remain unaffiliated with any movement at all.

In the face of tremendous defections from classic halakhic Judaism, the Orthodox community fought valiantly to maintain the time-honored beliefs and observances which they had inherited from their ancestors. But the Orthodox responses to the challenges of the modern situation were not monolithic. Some advocated a rejectionist stand, arguing that modern Western culture was to be eschewed to the extent possible. The "outside world," including non-Orthodox society, presented a danger to the purity of Jewish religious tradition; isolation was the best approach for Jews who wished to remain loyal to Torah and halakha. On the other hand, another Orthodox approach called for the active participation of Jews in general society while at the same time maintaining a strict allegiance to halakha. The task was to keep a balance of Torah with derekh eretz (worldly concerns/culture), Torah with madda (general knowledge).

These attitudes within Orthodoxy, as well as variations within the themes, have characterized Orthodox Jewish life since the mid-nineteenth century.

The strength of Orthodoxy has been its heroic devotion to Torah and halakha, even in the face of criticism and hostility. Orthodoxy alone maintains a total commitment to the Divine nature of the Torah and the binding authority of halakha. Orthodoxy is inextricably bound to all past generations of Torah observant Jews, and is faithfully confident that with the coming of the Messiah all Jews will return to traditional Torah life. Yet, it is the peculiar genius of Modern Orthodoxy to be thoroughly loyal to Torah and halakha while being open to modern thought and participating creatively in society.

Non-Orthodox detractors accuse Orthodoxy of being too bound by tradition, inflexible, unreceptive to modernity.

Non-Orthodox Jews have often found it expedient to stereotype Orthodox Jews as being "pre-modern," narrow-minded, irrational, insular, those who use religion as an escape from the realities of the world. They criticize Jewish law as being dry and tedious. They describe followers of halakha as unthinking slaves of ritual and detail, lacking in deeper spiritual feelings.

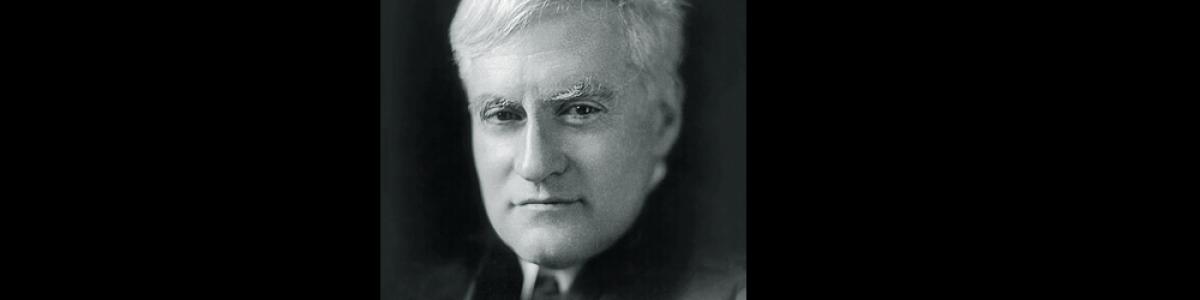

These criticisms and stereotypes are refuted in one name: Rabbi Joseph Baer Soloveitchik.

The Rav and Modernity

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, known to his students and followers as the Rav (the rabbi par excellence), is Orthodoxy's most eloquent response to the challenges of modernity and to the critics of Modern Orthodoxy. A Torah giant of the highest caliber, the Rav was also a world-class philosopher. In his studies in Lithuania, he attained the stature of a rabbinic luminary. At the University of Berlin, he achieved the erudition of a philosophical prodigy.

A Talmudic dictum teaches that the path of Torah is flanked on the right by fire and on the left by ice. If one moves too far to the right, he is consumed by fire. If he moves too close to the left, he freezes to death. Rabbi Soloveitchik was that model personality who walked the path of the Torah, veering neither to the right nor to the left.

The Rav's unique greatness made him the ideal symbol and spokesman of Modern Orthodoxy. In his own person, he demonstrated that the ideal Torah sage is creative, open-minded, compassionate, righteous, visionary, realistic and idealistic. He showed that one could be profoundly committed to the world of Torah and halakha and at the same time be a sophisticated modern thinker. Rabbi Soloveitchik was the paradigmatic 20th century figure for those seeking mediation between classic halakhic Judaism and Western modernity. He was the spiritual and intellectual leader of Yeshiva University, the Rabbinical Council of America and Mizrachi; his influence, directly and through his students, has been ubiquitous within Modern Orthodox Jewish life. He was the singular rabbinic sage of his generation who was deeply steeped in modern intellectual life, who understood modernity on its own terms; he was, therefore, uniquely qualified to guide Orthodoxy in its relationship with modernity.

The Rav was appreciative of many of the achievements of Western civilization. But he could not ignore the shortcomings of modernity. He was pained by the discrepancy between dominant modern values and the values of traditional religion. It is lonely being a person of faith in "modern society which is technically-minded, self-centered, and self-loving, almost in a sickly narcissistic fashion, scoring honor upon honor, piling up victory upon victory, reaching for the distant galaxies, and seeing in the here-and-now sensible world the only manifestation of being" ("The Lonely Man of Faith," p. 8). Utilitarianism and materialism, as manifestations of the modern worldview, are inimical to the values of religion.

In pondering the dilemma of a person of faith, the Rav explores a universal dilemma of human beings: inner conflict. He draws on the Torah's descriptions of the creation of Adam to shed light on human nature. Adam I is majestic; he wants to build, to control, to succeed. He is dedicated to attaining dignity. Adam II is covenantal; he is introspective, lonely, in search of community and meaning. He seeks a redeemed existence. Each human being, like Adam, is an amalgam of these conflicting tendencies. In creating humans in this way, God thereby underscored the dual aspect of the human personality. Human fulfillment involves the awareness of both Adams within, and the ability to balance their claims.

The Rav suggests that Western society errs in giving too much weight to Adam I. The stress is on success and control, pragmatic benefits. Even when it comes to religion, people seem to be more concerned with operating quantifiably successful institutions rather than coming into a relationship with God. In the words of the Rav: "Western man diabolically insists on being successful. Alas, he wants to be successful even in his adventure with God. If he gives of himself to God, he expects reciprocity. He also reaches a covenant with God, but this covenant is a mercantile one. ... The gesture of faith for him is a give-and-take affair" ("The Lonely Man of Faith," p. 64). This attitude is antithetical to authentic religion. True religious experience necessitates surrender to God, feelings of being defeated--qualities identified with Adam II.

By extension, the Rav is critical of modernizers and liberalizers of Judaism who have tried to "market" Judaism by changing its content. Any philosophy of Judaism not firmly rooted in halakha is simply not true to Judaism. The non-halakhic movements did not grow out of classic Judaism; rather, they emerged as compromising responses to modernity. Had it not been for the external influences on Western Jews, non-halakhic movements would not have arisen as they did. The litmus test of an authentic philosophy of Judaism is: is it true to Torah and halakha, does it spring naturally and directly from them, is it faithful to their teachings? If Torah and halakha are made subservient to external pressures of modernity, this results in a corruption of Judaism.

Modernity, then, poses serious problems for traditional religion. However, counter-currents within modernity offer opportunities. Already in the early 1940's, Rabbi Soloveitchik felt that the time had come for a new approach to the philosophy of religion. The "uncertainty principle" of quantum physics was an anodyne to the certainty of Newtonian physics. Thinkers in psychology, art and religion were proclaiming that human beings are not machines, but are complex organisms with religious, emotional and aesthetic sensibilities. Rationalism could not sustain and nourish the human soul. The Holocaust exploded the idealized myths of Western humanism and culture. Western civilization was moving into a post-modern phase which should be far more sympathetic to the spiritual character of human beings, more receptive to the eternal teachings of religion.

The Rav felt that a philosophy of Judaism rooted in Torah and halakha needed to be expressed in modern terms. Orthodox Jews needed to penetrate the eternal wisdom of the halakhic tradition, deepening their ability to cope with the challenges and opportunities of modernity and post-modernity. And non-Orthodox Jews needed to study classic Judaism on its own terms, freed from the negative propaganda of anti-Orthodox critics. After all, Torah and halakha are the patrimony of all Jews.

In his various lectures and writings, the Rav has provided a meaningful and powerful exposition of halakhic Judaism. He is a modern thinker, rooted in tradition, who has laid the foundation for post-modern Jewish thought.

Conflict and Creativity

The Rav has stated that "man is a great and creative being because he is torn by conflict and is always in a state of ontological tenseness and perplexity." The creative gesture is associated with agony ("Majesty and Humility," p. 25). As the Rav pointed out in "The Lonely Man of Faith," God created human beings with a built-in set of conflicts and tensions; this inner turmoil is a basic feature of the human predicament.

Religion is not an escape from conflict: it is a way of confronting and balancing the tensions that go with being a thinking human being. One must learn to be a creative free agent and, at the same time, an obedient servant of God.

Detractors of religion often portray religionists as seeking peace of mind by losing themselves in the spiritual realm.

Critics say: "it is easy to be religious; you do not have to think; you only have to accept the tenets of faith and you can avoid the responsibility of making decisions and facing conflict." To such critics, the Rav would say simply: you do not understand the true nature of religion. Religion is not a place for cowards to hide; it is a place for courageous people to face a totally honest revelation of their own inner being. Halakhic Judaism does not shield the Jew from ontological conflict: it compels him to face it directly, heroically.

It is precisely this inner tension and struggle which generates a lofty and creative understanding of life. Rabbi Soloveitchik's writings and lectures are vivid examples of religious struggle and creativity at their best. His use of typologies, his first-person reminiscences, his powerfully emotive use of language--all contribute to express his singular message: a religious person must live a creative, heroic life.

In his Ish ha-Halakha (Halakhic Man), the Rav notes that the halakhic Jew approaches reality with the Torah, given at Sinai, in hand. "Halakhic man, well furnished with rules, judgments, and fundamental principles, draws near the world with an a priori relation. His approach begins with an ideal creation and concludes with a real one" (Halakhic Man, p. 19). Intellectual effort is the hallmark of the ideal religious personality, and is a sine qua non of understanding the halakhic enterprise.

The Rav compares the domain of theoretical halakha with mathematics. The mathematical theoretician develops a system in the abstract; this theoretical construct is then applied to the practical world. The theoretical system helps define and shape practical reality. So it is with halakha. The classic halakhists immerse themselves in the world of theoretical halakha and apply halakhic constructs to the mundane world. The Rav observes that "both the halakhist and the mathematician live in an ideal realm and enjoy the radiance of their own creations" (Halakhic Man, p. 25).

The ideal halakhic personality lives in constant intimacy with halakha. Halakha is as natural and central to him as breathing. His concern for theoretical halakha is an expression of profound love and commitment to the entire halakhic worldview. This love and commitment are manifested in a scrupulous concern for the observance of the rules of practical halakha.

The sage who attains the highest level of relationship with halakha is one "to whom the Torah is married." This level is achieved not merely by intellectual acumen, but by imagination and creativity. "The purely logical mode of halakhic reasoning draws its sustenance from the pre-rational perception and vision which erupt stormily from the depths of this personality, a personality which is enveloped with the aura of holiness. This mysterious intuition is the source of halakhic creativity and innovative insight . . . . Creative halakhic activity begins not with intellectual calculation, but with vision; not with clear formulations, but with unease; not in the clear light of rational discourse, but in the pre-rational darkness" (Besod ha-Yahid ve-haYahad, p. 219). The halakhic personality, then, is characterized by conflict, creativity, imagination, vision. The world of halakha is vast and all-encompassing. One who reaches the level of being "married" to the Torah and halakha has come as close to eternal truth as is possible for a human being.

Halakhic Activism

Rabbi Soloveitchik emphasized the Torah's focus on this-worldy concerns. "The ideal of halakhic man is the redemption of the world not via a higher world but via the world itself, via the adaptation of empirical reality to the ideal patterns of halakha. ... A lowly world is elevated through the halakha to the level of a divine world" (Halakhic Man, pp. 37–38).

Whereas the universal homo religiosus believes that the lower spiritual domain of this world must yearn for the higher spiritual realms, halakhic man declares that "the higher longs and pines for the lower." God created human beings to live in this world; in so doing, He endowed human life in this world with dignity and meaning.

Halakha can be actualized only in the real world. "Halakhic man's most fervent desire is the perfection of the world under the dominion of righteousness and loving-kindness--the realization of the a priori, ideal creation, whose name is Torah (or halakha), in the realm of concrete life" (Halakhic Man, p. 94). The halakhic life, thus, is necessarily committed to this-worldly activism; the halakhic personality is devoted to the creation of a righteous society.

The halakha is not confined to sanctuaries, but "penetrates into every nook and cranny of life." Halakha is in the home, the marketplace, the banquet hall, the street, the office--everywhere. As important as the synagogue is, it does not occupy the central place in halakhic Judaism. Halakha is too vast and comprehensive to be confined to a synagogue.

Rabbi Soloveitchik argues that non-halakhic Judaism erred grievously in putting the temple at the heart of religion. "The halakha, the Judaism that is faithful to itself ... which brings the Divine Presence into the midst of empirical reality, does not center about the synagogue or study house. These are minor sanctuaries. The true sanctuary is the sphere of our daily, mundane activities, for it is there that the realization of the halakha takes place" (Halakhic Man, pp. 94-5).

Consequently, halakhic Judaism is realistic, idealistic and demanding. Halakha is concerned with every moment, with every place. Its sanctity fills the universe.

Halakha is unequivocally committed to righteous, ethical life. The Rav points out that the great sages of halakha have always been known for their lofty ethical standards. The halakha demands high respect for the dignity of others. "To recognize a person is not just to identify him physically. It is more than that: it is an act of identifying him existentially, as a person who has a job to do, that only he can do properly. To recognize a person means to affirm that he is irreplaceable. To hurt a person means to tell him that he is expendable, that there is no need for him. The halakha equated the act of publicly embarrassing a person with murder" ("The Community," p. 16).

The ethical demands of halakha are exacting. One's personal life must be guided by halakhic teachings in every situation, in every relationship. The halakhic worldview opposes mystical quietism which is tolerant of pain and suffering. On the contrary, halakhic Judaism "wants man to cry out aloud against any kind of pain, to react indignantly to all kinds of injustice or unfairness" ("Redemption, Prayer, Talmud Torah," p. 65; see also, U-Vikkashtem mi-Sham, p. 16). The Rav's stress on ethical activism manifested itself in his views on religious Zionism. He accepted upon himself the mantle of leadership for religious Zionism; this placed him at odds with many Orthodox leaders who did not ascribe religious legitimacy to the State of Israel. Rabbi Soloveitchik eloquently insists that the halakha prohibits the missing of opportunities. After the Holocaust, the Jewish people were given the miraculous opportunity to re-establish a Jewish state in the land of Israel. For centuries, Jews had prayed for the return of Jewish sovereignty in Israel. Now, in this generation, the opportunity was being offered. For the Rav, it would be tragic and unforgivable to miss the gift of the moment. Not to respond to "the knocking of the beloved," not to respond to God's message to the suffering people of Israel--this would be a tragic error of terrible magnitude. This was not a time for hesitation: this was a time to embrace the opportunity of a Jewish State, an opportunity granted to us by the Almighty. The Rav conveyed a certain impatience with those who did not respond religiously to the new Jewish State. Like the Shulamith maiden in the Song of Songs, they were drowsy and hesitant at the very moment the beloved had returned. They were not fully awake to the significance of the moment, and the halakhic and ethical imperatives which flowed from it.

Interiority

All true religious action must be accompanied by appropriate inner feelings and thoughts. The exterior features of religious behavior must be expressions of one's interior spiritual sensibilities.

Yet in non-Orthodox circles, it has long been fashionable to deride halakhic Jews as automatons who slavishly adhere to a myriad of ancient rules and regulations. They depict Orthodox Jews as unspiritual beings who only care about the letter of the law, who nitpick over trifling details, whose souls are lost in a labyrinth of medieval codes of law. To such critics, Rabbi Soloveitchik would answer quite simply: you do not understand the halakha; you do not understand the nature of halakhic Judaism. Interiority is a basic feature of the halakhic way of life.

Halakha relates not merely to an external pattern of behavior. Rather, it infuses and shapes one's inner life. "The halakha wishes to objectify religiosity not only through introducing the external act and the psychophysical deed into the world of religion, but also through the structuring and ordering of the inner correlative in the realm of man's spirit" (Halakhic Man, p. 59).

For the halakhic Jew, halakha is not a compilation of random laws; it is the expression of God's will. Through halakha, God provides a means of drawing nearer to Him, even of developing a sense of intimacy with Him. To the outsider, a person fulfilling a halakhic prescription may seem like an unthinking robot; but this skewed view totally ignores the inner life of the halakhic Jew. It does not see or sense the inner world of thought, emotion, spiritual elevation.

The halakhic Jew must expect to be misunderstood. How can others who do not live in the world of halakha possibly understand the profundity of halakhic life? How can those who judge others by surface behavior be expected to penetrate into the mysterious depths of a halakhic Jew's inner life? Those who stereotype Orthodoxy are thereby revealing their own ignorance of the true halakhic personality.

"Halakhic man does not quiver before any man; he does not seek out compliments, nor does he require public approval. ... He knows that the truth is a lamp unto his feet and the halakha a light unto his path" (Halakhic Man, p. 89). The halakhic personality strives to maintain and develop inner strength. One must have the courage and self-confidence to be able to stand alone. Self-validation comes from within one's self, not from others. "Heroism is the central category in practical Judaism." The halakhic Jew needs the inner confidence "which makes it possible for him to be different" ("The Community," p. 13).

Knesset Israel

Halakhic Jews feel inextricably bound to all Jews, even those who are unsympathetic to them and their beliefs. "Judaism has stressed the wholeness and the unity of Knesset Israel, the Jewish community. The latter is not a conglomerate. It is an autonomous entity, endowed with a life of its own .... However strange such a concept may appear to the empirical sociologist, it is not at all a strange experience for the halakhist and the mystic, to whom Knesset Israel is a living, loving and suffering mother" ("The Community," p. 9). In one of his teshuvah lectures, Rabbi Soloveitchik stated that "the Jew who believes in Knesset Israel is the Jew who lives as part of it wherever it is and is willing to give his life for it, feels its pain, rejoices with it, fights in its wars, groans at its defeats and celebrates its victories" (Al ha-Teshuvah, p. 98). By binding oneself to the Torah, which embodies the spirit and destiny of Israel, the believer in Knesset Israel thereby is bound to all the generations of the community of Israel, past, present and future.

The Rav speaks of two types of covenant which bind Jews to Knesset Israel. The berit goral, the covenant of fate, is that which makes a Jew identify with Jewishness due to external pressure. Such a Jew is made conscious of Jewish identity when under attack by anti-Semites; when Israel is threatened by its enemies; when Jews around the world are endangered because of their Jewishness. The berit goral is connected to Jewish ethnicity and nationalism; it reminds the Jew that, like it or not, he is a Jew by fate.

The berit yeud, the covenant of mission and destiny, links the Jew to the positive content of Jewishness. He is Jewish because he chooses the Jewish way of life, the Torah and halakha; he seeks a living relationship with the God of Israel. The berit yeud is connected with Jewish ideals, values, beliefs, observances; it inspires the Jew to choose to live as a Jew. The berit goral is clearly on a much lower spiritual level than the berit yeud; the ideal Jew should see Jewish identity primarily in the positive terms of the berit yeud. However, the Rav does not negate the significance of the berit goral. Even if a Jew relates to Jewishness only on the ethnic level, this at least manifests some connection to the Jewish people. Such individuals should not be discounted from Knesset Israel, nor should they be disdained as hopelessly lost as Jews. Halakhic Jews, although they cling to the berit yeud, must recognize their necessary relationship with those Jews whose connection to Jewishness is on the level of berit goral.

Ultimately, though, Jewish tradition is passed from generation to generation by those Jews who are committed to Torah and halakha. Thus, it is critical that all Jews be brought into the category of those for whom Jewishness is a positive, living commitment. Jewishness based on ethnicity will not ensure Jewish continuity. The Rav credited the masorah community with transmitting Judaism from generation to generation. The masorah community is composed of those Jews for whom transmission of Torah and halakha is the central purpose of life. It was founded by Moses and will continue into the times of the Messiah. Members of the masorah community draw on the traditions of former generations, teach the present generation, plan for future generations. "The masorah community cuts across the centuries, indeed millenia, of calendaric time and unites those who already played their part, delivered their message, acquired fame, and withdrew from the covenantal stage quietly and humbly, with those who have not yet been given the opportunity to appear on the covenantal stage and who wait for their turn in the anonymity of the 'about to be'" ("The Lonely Man of Faith," p. 47).

The masorah community actually embodies two dimensions--the masorah community of the fathers and that of the mothers. The Rav clarifies this point by a personal reminiscence. "The laws of Shabbat, for instance, were passed on to me by my father; they are part of mussar avikha. The Shabbat as a living entity, as a queen, was revealed to me by my mother; it is a part of torat imekha. The fathers knew much about the Shabbat; the mothers lived the Shabbat, experienced her presence, and perceived her beauty and splendor. The fathers taught generations how to observe the Shabbat; mothers taught generations how to greet the Shabbat and how to enjoy her twenty-four hour presence" (“Tribute to the Rebbitzen of Talne," p. 77).

The Rav teaches that Knesset Israel is a prayerful community and a charitable community. "It is not enough to feel the pain of many, nor is it sufficient to pray for the many, if this does not lead to charitable action" ("The Community," p. 22). A responsible member of Knesset Israel must be spiritually awake, must be concerned for others, must work to help those in need. "The prayerful-charity community rises to a higher sense of communion in the teaching community, where teacher and disciple are fully united" ("The Community," p. 23). The community must engage in teaching, in transmitting, in passing the teachings of Torah to new generations.

The Rav, Our Teacher

The Rav, through his lectures and writings, was the most powerful and effective teacher of Orthodoxy of our times. In his lectures, he was able to spellbind huge audiences for hours on end. His Talmudic and halakhic lessons pushed his students to the limits of their intellects, challenging them to think analytically. His insights in Torah were breathtaking in their depth and scope. Those who were privileged to study with him cherish their memories of the Rav. And those who have read his writings have been grateful for the privilege of learning Torah from one of the Torah giants of our time.

The Rav described his own experience when he studied Talmud. "When I sit to 'learn' I find myself immediately in the fellowship of the sages of tradition. The relationship is personal. Maimonides is at my right. Rabbenu Tam at the left. Rashi sits at the head and explicates the text. Rabbenu Tam objects, the Rambam decides, the Ra'abad attacks. They are all in my small room, sitting around my table."

Learning Torah is a trans-generational experience. It links the student with the sages of all previous generations. It creates a fellowship, a special tie of friendship and common cause. It binds together the community in a profound bond of love, and provides the foundation for future generations. Halakhic Judaism represents a millennial Jewish tradition dedicated to Torah and halakha, truth and righteousness, love and fear of God. It demands--and yearns to bring out--the best in us. One who strives to be a member of the trans-generational community does not suffer from spiritual homelessness.

When we and future generations sit down to study Torah, we will be privileged to share our room with Rashi and Maimonides, with Rabbenu Tam and the Rashba. And sitting right next to us will be Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, his penetrating insights leading us to greater heights in our quest to become "married" to the Torah.

References

Al ha-Teshuvah, written and edited by Pinchas Peli, Jerusalem, 5735.

Besod ha-Yahid ve-ha-Yahad, edited by Pinchas Peli, Jerusalem, 5736.

"The Community," Tradition 17:2 (1978), pp. 7–24.

"Confrontation," Tradition 6:2 (1964), pp. 5–29.

Halakhic Man, translated by Lawrence Kaplan, Philadelphia, 1983.

"The Lonely Man of Faith," Tradition 7:2 (1965), pp. 5–67.

"Majesty and Humility," Tradition 17:2 (1978), pp. 25–37.

"Redemption, Prayer and Talmud Torah," Tradition 17:2 (1978), pp. 55–72.

"A Tribute to the Rebbitzen of Talne," Tradition 17:2 (1978), pp. 73–83.

"U-Vikkashtem mi-Sham," Hadarom, Tishri 5739, pp. 1–83.